Learning Outcomes

Students will be able to:

i. Define the concept of a refrigerator and explain its function of extracting heat from a low-temperature reservoir and rejecting it to a high-temperature reservoir.

ii. Understand that a refrigerator operates in reverse to an ideal heat engine, requiring work input to maintain a temperature difference between its interior and the surroundings.

iii. Explain the relationship between the coefficient of performance (COP) of a refrigerator and the temperatures of the hot and cold reservoirs.

iv. Recognize the limitations of refrigerators due to energy dissipation and the need for continuous work input.

Introduction

In the grand orchestra of nature, heat flows from hot to cold, a natural tendency that shapes the world around us. Refrigerators, ingenious devices that defy this natural tendency, stand as testaments to human ingenuity and our quest for control over temperature. These devices, operating in reverse to heat engines, extract heat from a low-temperature reservoir, such as the interior of a refrigerator, and reject it to a high-temperature reservoir, typically the surrounding air.

i. The Symphony of Heat Transfer: A Refrigerator in Action

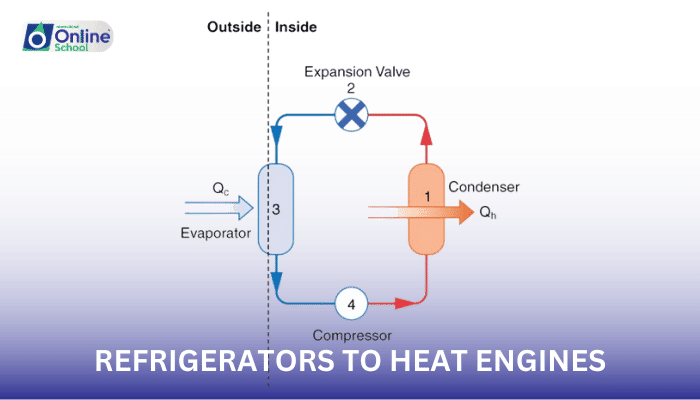

Imagine a refrigerator filled with food items. A refrigerant, a special fluid circulating within the refrigerator, absorbs heat from the interior, causing its temperature to decrease. The refrigerant then travels to a condenser, where it releases the absorbed heat to the surroundings, causing the temperature of the surroundings to increase slightly. This cycle of heat absorption and rejection forms the basis of a refrigerator's operation.

ii. A Symphony of Work and Efficiency: The Coefficient of Performance

Unlike heat engines that convert heat into mechanical work, refrigerators require work input to operate. This work is typically provided by an electric motor that drives the compressor, the device responsible for circulating the refrigerant. The coefficient of performance (COP) of a refrigerator is a measure of its efficiency, defined as the ratio of the heat extracted from the low-temperature reservoir to the work input required.

The COP of a refrigerator is directly related to the temperatures of the hot and cold reservoirs. A larger temperature difference between the reservoirs results in a higher COP, indicating a more efficient refrigerator.

iii. Limitations and Implications: A Symphony of Challenges

Refrigerators, while essential appliances, are not without their limitations. Energy dissipation, primarily due to friction and heat transfer through the refrigerator walls, reduces the efficiency of the device. Additionally, refrigerators require continuous work input to maintain the temperature difference between the interior and the surroundings.Despite these limitations, refrigerators have revolutionized food preservation and storage, enabling us to enjoy fresh produce throughout the year. Their development and improvement have been crucial for modern food distribution and consumption practices.

Refrigerators, the unsung heroes of our kitchens, operate in a symphony of heat transfer, work input, and efficiency. While they defy the natural tendency of heat to flow from hot to cold, they require continuous work input and face challenges due to energy dissipation. Nevertheless, their impact on our lives is undeniable, enabling us to preserve food, maintain a comfortable environment, and enjoy a variety of culinary delights. As we continue to explore the universe, the principles of refrigeration remain guiding principles, illuminating the path to new discoveries and advancements in our quest for sustainable cooling solutions.